Victoria Anna Perea entered the history of Spanish medicine from the moment she was born. On July 12, 40 years ago, at the Dexeus clinic in Barcelona, this baby weighing almost two and a half kilos became the first person in Spain to be born after an in vitro fertilisation process. The media across the country rushed to report on this scientific milestone and continued to portray her growth over the last four decades. Until today. “As far back as I can remember, journalists came to the house on birthdays. My parents told me it was because I was born in a special way. And as I grew up, I began to understand it. We always talked about it very naturally,” she says on the other end of the phone. Her birth illuminated the first steps of assisted reproduction, a discipline that, after 40 years of development and 12 million children born thanks to it, has reached maturity with less invasive techniques, more effective procedures and a change in the profile of patients.

EFE

The first children born through assisted reproduction were called test tube babies. The first success story in the world, that of the British Louise Brown in 1978, made headlines around the world and even today you can watch her birth on YouTube. Perea’s case, on a smaller scale, replicated the media attention. “It was a shock,” recalls today Pedro N. Barri, president of the Dexeus Mujer Foundation and head of the Reproduction service team that achieved the first birth by in vitro fertilization (IVF) in Spain. “At that time, a kind of procreation show was generated. It was a health issue that changed something very traditional, which was the way we humans reproduce. We were proposing a medical treatment for a medical problem.” [la madre de Perea, como la de Brown, tenían problemas en las trompas de falopio que impedían el embarazo]but it had to be reasoned very carefully. The only way to dismantle the procreation spectacle was to explain it a lot,” he says.

Before those first steps in assisted reproduction techniques, Barri recalls, there was nothing. Against infertility, “alchemy and quackery,” he says. And it took a while to smooth out the rough edges and suspicions on the street – the Catholic Church even published an encyclical in which it spoke out against assisted reproduction. But science won out and those first babies born after IVF soon became thousands. And over time, millions. “It has become normal. In every family or group of friends there is a case,” Barri concludes.

The progress was dazzling. The year Victoria Anna was born, three children were born at Dexeus using these techniques. When the young woman turned 25, in 2009, the then president of the Spanish Fertility Society (SEF), Buenaventura Coroleu, pointed out to EL PAÍS that children born in Spain each year with the help of a “laboratory stork” already accounted for 2% of all births. And the curve continued to rise: in 2021, more than 40,000 children were registered as conceived with the help of these techniques and they now represent 12% of all births.

Assisted reproduction is not what it was in those early years. It has been perfected in the heat of scientific advances and social changes that demanded new needs. In fact, the profile of patients is not what it used to be either: according to Dexeus’ calculations, in the beginning, they were women of about 35 years old, with a partner, who came for problems in the fallopian tubes that prevented pregnancy; now, the average age has advanced to 38 years old – 50% of its patients are over 40, when in 1995 this profile was only 11% – and the main indication for these treatments is late maternal age, which also makes pregnancy difficult. There are also more women who want to be single mothers and lesbian couples who resort to this technique.

Age is, in any context, yesterday and today, a key element. It is the main factor for success and, at the same time, the reason for the need to resort to these procedures when motherhood is delayed. “Women, from the age of 35, enter the perimenopausal transition in which the ovaries begin to function worse, both in vivo and in vitro fertilisation. And there is a greater risk of miscarriage,” Barri explains. The younger the woman, the greater the chance of success.

Late maternal age

Victoria Anna Perea has suddenly become the paradigm again. As she was then the paradigm of the success of assisted reproduction, today, at 40 years old, she is the mirror of a generation that has delayed the age of motherhood. “I live it as a contradiction. I am the result of a success story, but I also have examples in my close environment where it does not always turn out well. I am the happy face, but it is a hard process, physically and emotionally. I am not a mother at the moment, I am considering it, but like many people of my generation, we delay it,” she says.

The process is complex and resorting to assisted reproduction does not guarantee pregnancy either. “No technique is a sure pregnancy, just as trying to do it naturally and getting pregnant the following month is not,” says the current president of the SEF, Juanjo Espinós. Scientific and technical improvements in assisted reproduction have improved success rates and, according to Dexeus, they have gone from between 20% or 25% when they started, to favourable results in up to 65% of cases. However, the president of the SEF asks not to cling to the figures: “It depends a lot on each case. The variability is very high, even between cycles of the same woman.” Perea calls for “making visible” the whole process and reinforcing the information “on what can happen.” Espinós sums up: “The treatments we do have no effects on health. The problem is expectations because you generate hopes and stress about the results and there can be significant frustration.”

In a context of global decline in fertility rates and increasing age of motherhood, techniques have also been refined to respond to new demands: increasingly less invasive approaches have been adopted and the process and selection of embryos have been perfected to achieve the desired pregnancy in the best conditions. “Before, egg extraction was done by laparoscopy, with general anesthesia, the woman was hospitalized for one day… It was very tedious. Now it is done with a vaginal puncture, sedation and after two hours she goes home. It is a less aggressive procedure,” Barri exemplifies. In addition to IVF, there is also artificial insemination, which is simpler, but indicated only for a specific profile of cases, the gynecologist points out, such as a young woman who wants to be a single mother and has to resort to donor sperm.

Studying the DNA of embryos

Another scientific leap that has revolutionised assisted reproduction was the appearance of preimplantation genetic diagnosis, which allowed the study of the DNA of embryos to identify malformations or genetic errors that could compromise their viability. In the early days, says Barri, this technique was used when one of the parents was a carrier of a genetic mutation that could be transferred to the baby, but today, with the change in the profile of patients, this tool has been key to improving the response to treatments: “Today, the main indication for which we do preimplantation genetic diagnosis is the advanced age of the woman, because in this context there is a higher percentage of abnormal eggs and embryos. So, if we identify and transfer only the normal embryos, we improve pregnancy rates.”

Science has also made progress in egg freezing – in the first IVFs, fresh transfers were made – which makes treatment easier, increases the chances of response and reduces the occurrence of multiple pregnancies. Thus, if previously an ovarian stimulation cycle ended with three useful embryos (the maximum allowed by law), all three were transferred at the same time, waiting for at least one to implant. If two or three were implanted, there was a multiple pregnancy. “Freezing has given us two or three possibilities of pregnancy because now, in 90% of cases, we transfer a single embryo and reduce multiple pregnancies, which have complications for the mother and the babies,” explains Barri.

The introduction of egg donation and egg preservation systems, on the other hand, have also played in favour of this shift in the social context of assisted reproduction. Again, explains the Dexeus gynaecologist, if previously egg donors were used, above all, to treat women without functioning ovaries or those who had had these organs removed, now the main indication is the advanced age of the woman.

The latest major advance in the field of fertility has been uterus transplants, an innovative technique that, although not free of controversy, has allowed pregnancies in women who did not have this organ. Last year, the first baby in Spain was born using this procedure at the Hospital Clínic in Barcelona.

The “black box” of assisted reproduction

Barri welcomes the maturity of this technique, but warns that much remains to be done. For example, discovering the mechanisms of the great “black box” of assisted reproduction, he says: that moment after the transfer in which the embryo and the uterus “talk” until it implants or not. There, scientists are blind. “We can control the entire cycle, the stimulation, monitor the process, the quality of the egg and the semen, the embryos… But when we do the transfer, there is a dark period in which we do not know if the implantation has failed or not.”

Assisted reproduction has become normalised, but it still raises controversy on certain points. Such as access to these procedures – in Spain it is part of the public service portfolio, but there are long waiting lists and most treatments are carried out in the private network – or the age limit: there is no figure, although the limit, says Barri, follows “medical” criteria: “Over the age of 45, we do not recommend treatments with one’s own eggs because the possibility of having a normal embryo and transferring it is minimal. And the law says that assisted reproduction techniques can be applied up to the biological age of fertility, that is, no more than 50 years.”

Genetic analysis of the embryo also poses challenges, due to the risk of playing a role in selection outside of strictly clinical contexts. Barri is blunt: “Preimplantation genetic diagnosis has only medical indications. Another thing are the collateral uses, such as sex selection, because we can know the sexual chromosomes: in Spain it is prohibited to select the sex of the embryo, but in other countries it is permitted.” The gynecologist assures that, beyond that, being able to choose whether the baby will be blond or dark-haired, with blue or green eyes, is “science fiction.” And if something like that happens, he points out: “It would be an aberration of the technique. What we have to convey to people is that science does not have to enter where nature acts well.”

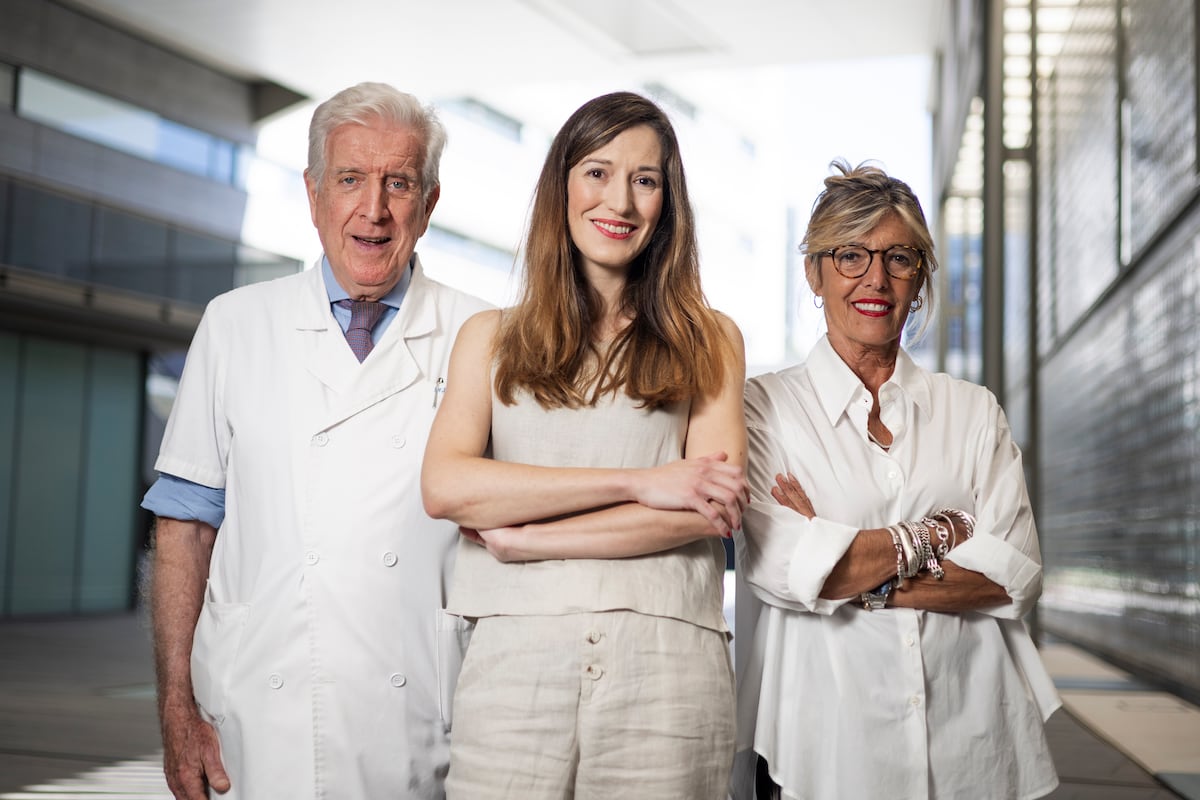

About to turn 40, Perea says she maintains strong ties with Barri and biologist Anna Veiga, her scientist parents. “It’s a very close relationship. Anna is like an aunt to me,” she says of Veiga. Her middle name, in fact, is in her honour.

You can follow THE COUNTRY Health and Wellbeing in Facebook, X and Instagram.