The following text is an excerpt from the book Why do we dream? And other great questions about sleep and sleepby Pablo Barrecheguren (Plataforma Editorial) recently published. It is a journey through the science of dreams, from lucid dreams to the impact of a good night’s sleep on health. Little by little, questions about sleep are being resolved, the simplest of all being: can we live without sleeping?

During the Christmas holidays of 1963, teenagers Randy Gardner and Bruce McAllister decided to take advantage of those days to start a science project: to see how long a person can go without sleeping. Apparently, Randy and Bruce played lots by tossing a coin who would be the one who would not sleep and who would monitor whether the experimental subject fell asleep or not. It was Randy’s turn to stay awake as long as possible. How long do you think he lasted?

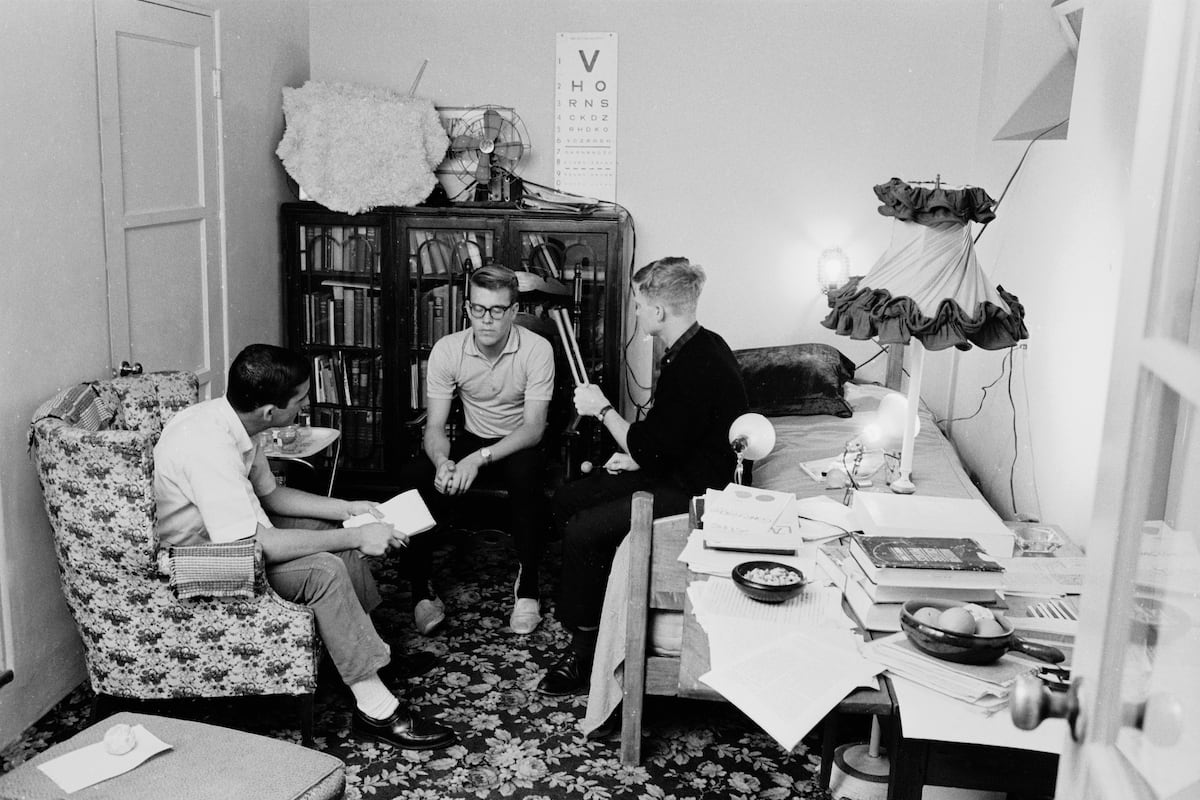

Since it was all very improvisational, the seventeen-year-olds soon realized that the work was too much for both of them, so they asked a colleague to help them monitor Randy, and within a few days they were joined by researcher William Dement from Stanford University, who was one of the pioneers in studying sleep at a clinical level. William had read about the boys’ science project in a newspaper and wanted to get involved, along with a doctor from the United States Navy, John J. Ross. This must have been quite a relief to Randy’s parents, since at that time there was no data to know what would happen, and I suppose some clinical supervision reassured them a little, although one might also wonder why no adult stopped Randy, since they really didn’t know what could happen.

Apparently, the main trick to keeping Randy awake was to keep him active by doing physical activities, especially basketball. In fact, I’ve even read that Randy improved his game throughout the days of enforced sleeplessness, although one possibility is that he simply improved because of the number of hours of daily practice he played. He was also given some tests to evaluate his cognitive abilities, his senses… and although Randy was initially optimistic, even cheerful, soon some things began to become apparent: starting on the third day, Randy began experiencing hallucinations, and after the first few days, his condition deteriorated. “There were no more ups, only downs and downs. It was like someone was sandpapering my brain. My body was dragging, and my mind was shattered,” he wrote.

It is documented that his perception abilities gradually became affected, he suffered changes in smell, memory problems, attention, mood swings, he progressively lost verbal agility, his memory worsened and his speech was also affected: it reached a point where he found it difficult to even talk because, among other things, he was so distracted that he was unable to hold a conversation. In these final moments, a point was reached where Randy was unable to do the cognitive tests that were put to him because he had such a poor ability to concentrate that he continually lost track of what he was doing. During the last day he is described as almost lethargic, expressionless and monotonous in speech. Finally, Randy fell asleep after 11 days and 25 minutes.

Randy slept for 14 hours straight before waking up to go to the bathroom. In the following days, his sleep pattern returned to normal and the evaluations carried out have not found that Randy suffers long-term consequences from the experience. However, this story has many drawbacks that prevent us from drawing conclusions: perhaps the most important is that it is very likely that Randy experienced microdreams, very brief moments in which his brain went from being awake (wake) to states of consciousness similar to being asleep, which from the outset would mean that Randy would not have been awake for more than 264 hours straight. Another relevant point is that, apparently, occasionally during those days he drank some Coca-Cola, so there was a little caffeine disrupting the experiment. Also, let’s remember that Randy was a teenager and, as we will see later, the sleep needs of a teenager are not the same as those of a child, a baby, an adult or an elderly person. We must also take into account both the technical limitations of the time and the fact that some factors, such as, for example, the supposed physical improvement while playing basketball, were not measured with adequate precision (at least for what is now considered rigorous). Which brings me to the last point, and that is that this experiment fails in many design points, among them one of the most obvious is that it is a project carried out by testing a single person, when the most preliminary investigations usually work with groups. of at least ten to twenty people (and this number can grow to tens of thousands of people, or even more). In short, on a technical level the experiment was botched, and highly criticizable on an ethical level. This is obviously not the fault of Randy or Brand, who had no neuroscientific training.

Although there are people who claim to have managed to beat Randy’s record (by a few hours, don’t expect anything too far from those eleven days without sleep), it is often said that no one is going to beat this record, since the institutions that record these Things, like the Guinness World Records, have not verified these types of marks for a long time to prevent someone from getting hurt trying it, since there is a fairly considerable real risk. And, for the same reason, there are no scientific experiments to see how long a person can go without sleep, so much of the information about what happens if a person loses the ability to sleep comes from clinical cases in which a sleep problem health generates a similar situation. Here patients with fatal familial insomnia or those suffering from Morvan syndrome stand out.

On the one hand, we have fatal familial insomnia; people who suffer from it die after 8 to 72 months from the onset of symptoms. The word “familial” refers to the fact that it is a hereditary disease, although very rare, since it is the rarest hereditary disease of prion proteins. These types of diseases, whether hereditary or not, and among which the best known is Creutzfeldt-Jakob, are characterized by the fact that the cause is a prion (a prion is a rather problematic type of protein that is capable of converting other similar proteins into prions, causing there to be more and more prions and fewer “normal” proteins). If we imagine proteins as different types of fruit, and each fruit is placed in a different basket, prions would be like a piece of rotten fruit: if, for example, an apple prion is placed in the basket of apples, little by little the apples (the apple proteins) around the prion will turn into rotten apples (new apple-type prions), which will rot the rest of the apples around them, and so on until the entire basket is rotten. Although there are still many points of origin of the disease that are not clear, the general idea is that in fatal familial insomnia patients inherit genetic changes that cause them to eventually produce the prions that generate the disease, which is characterized by a series of symptoms, among which profound insomnia stands out.

On the other hand, we have Morvan syndrome, which is a completely different situation because it is an autoimmune disease, that is, caused by a malfunction of the patient’s immune system. There are very few documented cases of this syndrome, which has a wide range of symptoms ranging from involuntary muscle contractions to painful muscle cramps, hallucinations, deep insomnia in most cases, and there are even cases that present other symptoms as disparate as constipation or excessive sweating. Insomnia is an important point of the syndrome, since it is present in almost 90% of cases, and the patient may experience very deep degrees of sleep loss, but, unlike what happens in fatal familial insomnia, in the vast majority of cases this disease is not lethal: nine out of ten cases end up remitting spontaneously, while 10% of patients die.

For many years, deaths from both Morvan syndrome and fatal familial insomnia have been used as a definitive argument that humans cannot survive without sleep. However, this statement is being discussed a lot because it has several weaknesses: perhaps, the main point is that they are very complex and quite unknown diseases in which patients develop many problems beyond insomnia, so it is not necessarily the lack of dream the cause of death. Furthermore, they are very exceptional situations: for example, there are only approximately twenty documented cases of Morvan syndrome that present sleep disorders. And, furthermore, there is quite a bit of complexity in specifying how insomnia occurs in these diseases, since sleep is not a homogeneous process and some parts of sleep may be failing more than others; to which we must add the possibility that patients may be experiencing microsleeps that, in part, alleviate their lack of sleep.

Pablo Barrecheguren He is a doctor in Biomedicine specialized in Neurobiology and author of Why do we dream? And other big questions about sleep and dreaming.

You can follow THE COUNTRY Health and Wellbeing in Facebook, X and instagram.