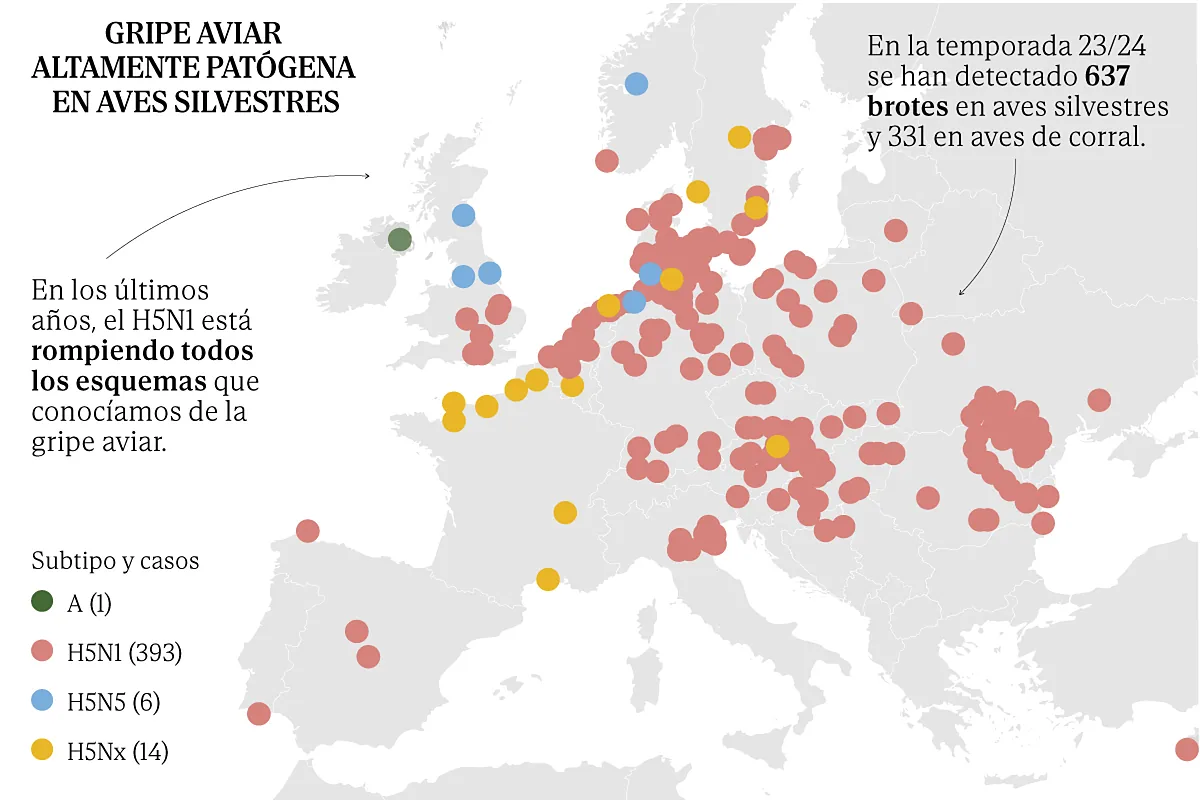

“We have to carry out very close surveillance because this virus is warning of its potential and we are increasingly climbing the risk scale.” As other experts in bird flu, Elisa Perez Ramirezresearcher at the Research CenterAnimal Health Investigation (CISA-INIA-CSIC), has been closely following the developments of the H5N1a virus “that is breaking all the patterns we knew about bird flu,” both because of its global distribution, its lethality in different animals and the large number of species it has managed to infect.

The epidemiological changes that the pathogen has experienced in a short time are so significant that “right now we are in a scenario of great uncertainty“And that is not good news,” continues this doctor in Veterinary Medicine, who points out that although the virus is still not very effective at infecting humans, its characteristics and potential make it an important threat to be taken into account.

At the moment, the risk in Spain for the general population is still considered very low, according to the latest assessment carried out by the Health Alerts and Emergencies Coordination Centre (CCAES) last May, but given the current situation, “it is necessary to maintain surveillance and public health measures, as well as reinforce the early diagnosis of possible human cases in the healthcare environment and investigate possible new transmission routes,” the agency said.

Since the 21/22 season, when this highly pathogenic avian influenza virus The pathogen has not only managed to wreak havoc on all types of wild and poultry birds, but has also managed to infect a large number of mammals, such as foxes, minks, dogs, raccoon dogs, cats and sea lions, among other species. But, without a doubt, the most worrying leap is the one the pathogen recently made in the USA, when it managed to reach cattle. The North American health authorities reported the first cases in March 2024; in three months, 137 herds of cows have been affected in 12 states.

In this short period of time in the country there have also been three human infectionsall of them due to direct contact with infected cows. The first of these cases, reported on April 1, was a worker on a farm in Texas who developed conjunctivitis. Tests subsequently confirmed infection by a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (specifically clade 2.3.4.4b) in the individual, who was treated with the antiviral oseltamivir and has recovered without developing further symptoms. Later, in May, two other cases were confirmed in Michigan, also in workers exposed to infected cows: one of them also suffered eye problems, while the second suffered mild respiratory symptoms. Both overcame the infection without incident.

«This situation is totally unexpected. “There had never been an infection in any type of ruminant before, so it raises a lot of questions,” says Pérez. For now, the US is the only place in the world where this jump to bovines has been detected. In Europe, there is currently no active surveillance of avian influenza in cattle, although “an outbreak would not go unnoticed,” says Pérez. In the US, alarm bells were raised due to a sharp drop in milk production and various non-specific symptoms among cattle, such as loss of appetite. “If it were happening here, we would have noticed it. We still don’t know why it has only happened in the US so far. It is something that will have to be investigated.”

Beware of raw milk

The detection of an avian flu virus in a type of domestic livestock such as cattle is worrying because of its proximity and the possibility that it could open the door to the virus adapting to humans. «There is evidence that the virus It can be transmitted through raw, unpasteurized milk. In experiments with mice, consumption of raw milk produced systemic infections, with the virus present throughout the body, including in the mammary glands of female mice,” says Pérez, who stresses that this is a danger that should be addressed now. “In the US there is a significant percentage of consumption of raw milk, which is always a bad idea due to the large number of infections that can be acquired. In that country it is legal to sell untreated milk, but with this risk of transmission of bird flu I think that The sale of raw milk should not be permitted under any circumstances.“, explains the researcher. The experiments carried out to date show that pasteurization does inactivate the virus.

According to Pérez, the epidemiological situation in the US also requires more exhaustive surveillance of people exposed to infected animals. “It is certain that there have been other cases in people because the symptoms are very mild and they have been able to go unnoticed,” says the scientist, who, like other critics in the US, believes that fewer tests than necessary are being carried out among workers on livestock farms in the US. “The first barrier we have to detect that a jump to humans is taking place is in the surveillance of people who work with infected animals. And it seems that in the US today Surveillance is not as good as it should bealso due to the reluctance of some workers,” he says.

To date, the sequences analysed from the virus, both in cattle and in affected workers, show that the pathogen still retains a strong preference for bird recipients rather than mammals, but the great mutation power of these viruses and their ability to recombine their genome requires close monitoring.Currently, H5N1 still has a hard time infecting humans.. There have been isolated cases of infection, but it is not sustained and there is no transmission between humans,” he stressed. Luis Mailboxspokesperson for the Spanish Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (SEIMC), who adds that the virus currently does not have the real capacity to efficiently infect human cells. “It lacks one issue, which is not minor, and that is that its hemagglutinin, the protein on its surface that allows it to infect, mutates and adapts to infect human cells. That has not happened to date and it is not a small leap for the virus.” The risk of the virus causing a pandemic “is low today but that does not mean that this situation cannot change in the coming months. And all of this depends on the capacity of the virus to adapt to humans. That is why It is key to try to avoid contact between humans and sick animals.“, he points out.

Influenza viruses are often mentioned among the pathogens most likely to cause a pandemic due to their characteristics. They are viruses that are transmitted through the air, have a great ability to mutate and can also reorganize their genome, which favors the emergence of variants with a greater capacity for transmission or for jumping to other species.

According to Buzón, the genome of these microorganisms has eight fragments of nucleic acids in the form of RNA that can recombine. Thus, if different influenza viruses co-infect the same cell, the genetic material of both can mix, giving rise to new variants. This recombination was what gave rise to pandemics such as that of 1918, he points out. Angela Dominguezmember of the Spanish Society of Epidemiology, who recalls that “there is no rule that says that if we have just gone through a pandemic it cannot happen again in 20 years.” The human population is susceptible to being attacked by a new virus against which it has no immunity, which is why “Epidemiological surveillance and preparation are so important”he points out.

The Spanish virologist Adolfo Garcia-Sastre He has been studying influenza for years at the Global Health and Emerging Pathogens Institute, which he directs at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. In his opinion, “it is certain that there will be a pandemic at some point caused by the influenza virus,” because this virus has already caused four pandemics in 100 years. “What we do not know is when, where and what variant it will generate,” he emphasizes. “H5N1 viruses are among the most widespread in the world and, therefore, more likely to cause a pandemic than other, less numerous avian influenza viruses, but we cannot know for sure,” explains the researcher, one of whose objectives is to develop a universal influenza vaccine that “can protect against any flu virus, whether H5N1 or otherwise.”

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recently recommended the authorisation of two vaccines aimed at preventing human infection with the H5N1 avian influenza virus, but these vaccines target a variant type and would have to be updated in the event that the virus were to be easily transmitted between humans. For this reason, García-Sastre’s team is developing a vaccine that aims to be universal, since it targets an area of the pathogen’s genome that remains unchanged, which does not change despite mutations.

In preclinical studies in animal models, these universal vaccines have shown that they “provide protection against infection and disease caused by any influenza virus, regardless of its origin,” explains the researcher. “Phase 2 and phase 3 studies with groups of volunteers of different ages, sexes and ethnic origins with a sufficient number of participants are still needed to be able to statistically prove that they protect against infection for at least several years,” but in order to be able to carry out all the studies, “It would require around 500 million euros and that is why progress is being made little by little”he clarifies.

“Now is not the time to let down our guard,” experts agreed. “Flu viruses have already shown what they are capable of too many times.”