Welcome to Impact Factoryour weekly dose of commentary on new research in medicine. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, New York.

Much of epidemiology begins with a simple question, but when you think about it, you realize how complicated it really is. Here’s a simple question: Is cancer more common today than in the past?

Easy, right? Well, let’s break it down. The truth is that there are more new cases of cancer in the United States now than ever before. Two million people were diagnosed with cancer last year in the country. In 1990, about a million were diagnosed. Of course, this is misleading; the U.S. population is now larger than it used to be. So we don’t really want a count, but rather a rate per 100,000 individuals.[1]

But even the incidence rate of cancer is not entirely clear. After all, the population of that country is now older than in 1960, for example, and age is the main risk factor for most cancers. If the rate of a certain cancer is increasing, is it really fair to conclude that something concerning is causing it if it’s really just due to the general aging of the population? As one of my epidemiology professors said, “The question is what the question is.” So if we really want to understand whether anything has fundamentally changed in terms of cancer risk over the years, we need to calculate age-adjusted cancer rates.

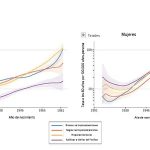

Still, there is a problem. Older people are not only biologically older, they were also born further back in time. I know this sounds like circular reasoning, but it’s a little deeper than it seems. You have to realize that today’s 70-year-olds were exposed to substances in the 90s, when they were 40 years old. And the current fifty-somethings had the same exposure, but when they were 20 years old. Therefore, birth cohort matters. If some horrible cancer-causing chemical was briefly released in 1992, for example, you would expect an increase in the disease among everyone alive in 1992, regardless of their age.

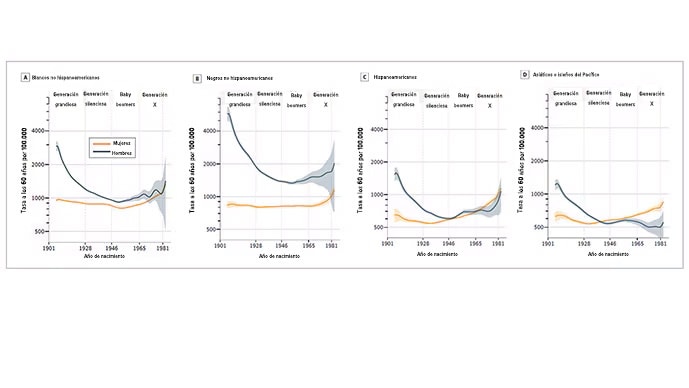

In fact, it may be reasonable to think of cancer incidence not in terms of calendar years, but in terms of risk per social generation. And if you do that analysis, you’ll find something quite interesting. With each successive generation from the baby boomerscancer incidence has declined, with one exception: Generation X.

Born in 1979, at the tail end of Generation Simpler times. From a public health standpoint, my generation was one of the first to clearly understand, from a very young age, the risk factors for cancer. We were told “just say no”, although the effect was not that profound.

We became more health conscious, although the “low fat” fad would prove disastrous as our carbohydrate intake skyrocketed. Even so, a priori would have thought our cancer rates would be lower than our parents’. This study by Trends in cancer incidence in successive social generations in the United States, published in JAMA Network Openshows us that this is not the case.[2]

The researchers used the well-known SEER cancer database to capture new cancer cases among 3.8 million people in the United States from 1992 to 2018. This cohort spanned the birth years 1908-1983, from the Great Generation to Generation X.

The key data are the age of cancer diagnosis and the year of birth. This allowed the team of researchers to examine how cancer rates at a given age changed over time.

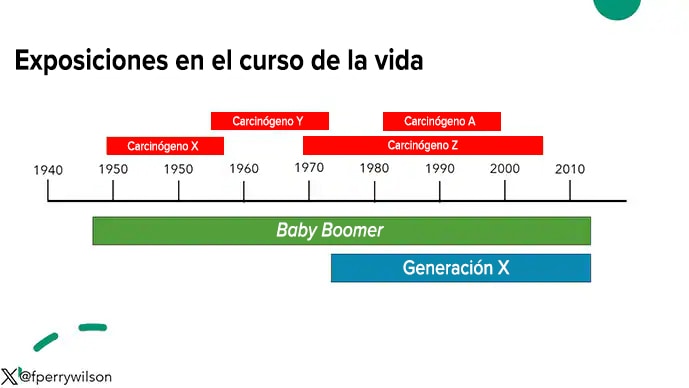

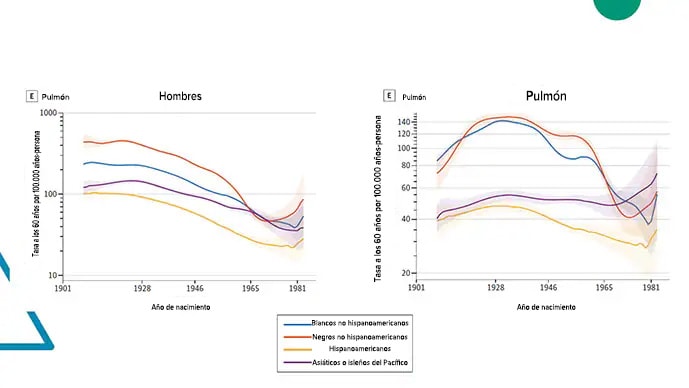

I’ll start with a simple example. Here are the lung cancer rates at age 60 for women and men, by year of birth. The general trend is pretty clear: people born in more modern times have a lower risk of developing lung cancer at age 60.

This makes sense. The anti-smoking campaign has been one of the most successful public health campaigns of the past 50 years.

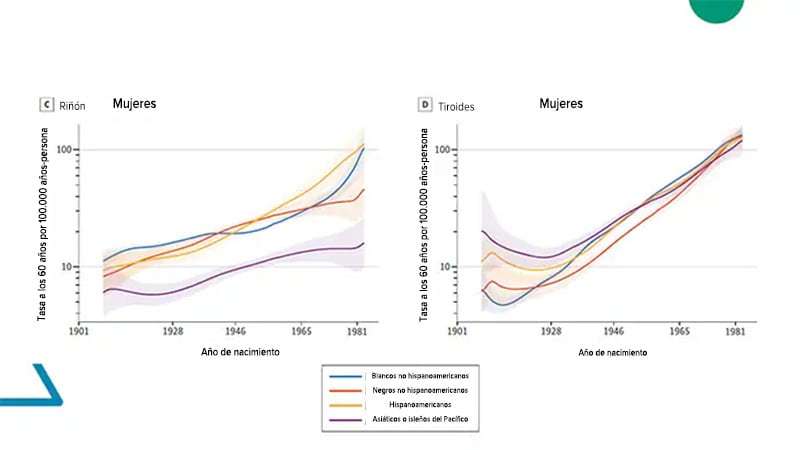

But the situation is not so good for other types of cancer. For example, look at the rate of kidney and thyroid cancers. People born at the turn of the century are much more likely to be diagnosed with thyroid or kidney cancer than previous generations.

Grouping the main types of cancer produces graphs like this one. The group of authors stratifies them by race and ethnicity, but the pattern more or less holds. The Great Generation had the highest risk of cancer, which decreased and remained more or less stable for the baby boomers And then, slowly and inexorably, it has begun to rise again, putting my generation – for the first time in a century – at greater risk of cancer than our parents.

Well, what’s going on here? There are some benign explanations – pardon the pun – over the past 100 years we’ve made a lot of progress in reducing the rate of heart disease in the population. As deaths from heart disease have declined, the number of people who live long enough to be diagnosed with cancer has increased. Of course, age-adjusted cancer rates should take this into account.

The fact that this study examines the number of new cancers detected is not considered, detected like the keyword here. As technology has advanced, our ability to detect cancers at an earlier stage, and even to detect cancers that would otherwise never have been detected, has increased dramatically. Thyroid cancer is a good example of this; As thyroid ultrasounds proliferate, incidentally detected thyroid cancers have skyrocketed.

Supporting the idea that it’s all about increased detection is the fact that, overall, cancer mortality has declined over time. Although I am more likely to be diagnosed with kidney cancer than my parents, I am less likely to die from it. That’s because of earlier detection, but also, of course, because we now have better treatments.

There are, of course, malignant explanations for this phenomenon. Environmental exposures have changed substantially from the 1940s to today, and the substances my generation was exposed to as children are fundamentally different from the substances my parents were exposed to. Sure, they had lead and tobacco smoke. But we had industrial chemicals, pesticides, and ultra-processed foods.

What this article really tells us is that the fight against cancer is not only continuing, but changing. I’ve seen it anecdotally in my own practice, younger and younger people are getting cancers that, according to the books I read in medical school, older people are supposed to get. We are making progress, of course, it is clearly better to have cancer now than it was 50 years ago, but the goal of eliminating cancer will force us to be flexible in our approach. Cancer changes quickly, we have to too.

He Dr. Perry Wilson, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Yale Clinical and Translational Research Program. His science communication work can be found on the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. His new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

This content was originally published in the English edition of Medscape.