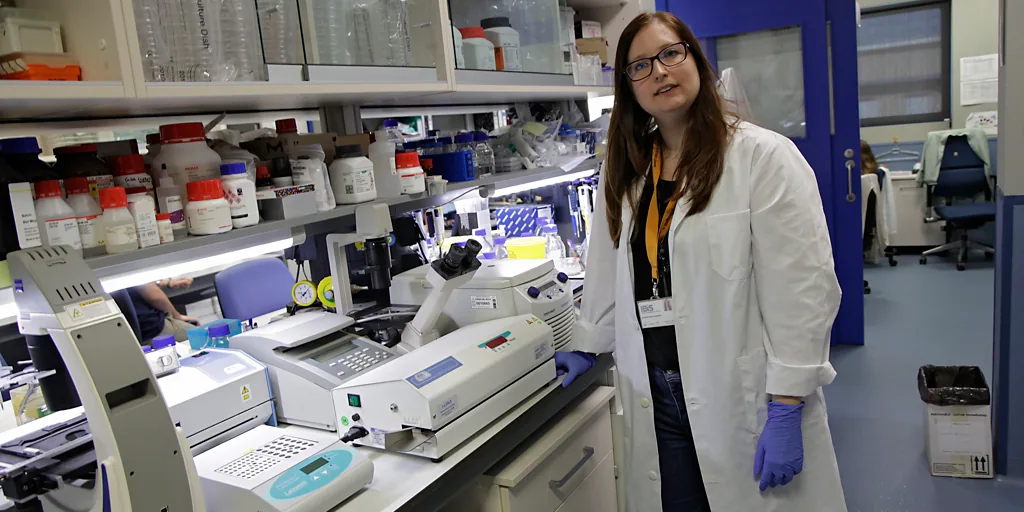

Stephanie Garcia Guerrero She is 36 years old, a biotechnologist from the Pablo Olavide University of Seville and one of the most recognized researchers of her generation in Andalusia. She has just received the Seville Medal for his research work in the Institute of Biomedicine … of Sevilla (IBIS) and the new designs for CAR-T therapy, a revolutionary treatment against lymphomas and other types of cancer discovered in the United States a decade ago and which is already beginning to be tested on brain tumors and even non-oncological cellular diseases.

-You were born and raised in Camas. What did you think when you received the Medal of Seville?

-The first thing that came to mind was my grandmother, who was everything to me. I have always had her in mind. I also remembered my parents and the team that supports me at the Institute of Biomedicine in Seville.

Does it all start in a laboratory?

-Yes. The origin of this medal (she proudly brought it to be photographed with it during the interview) is in the laboratory. Ideas emerge in the laboratory and with effort, work and sacrifice, and thanks to institutional support, you manage to treat patients and cure them. I have sacrificed many things for research and I have even put my personal life aside a little. I have prioritized my work above all else, to which I dedicate many hours in the laboratory.

-She is married but has no children. Is it easy to balance personal and family life at work?

-If you dedicate yourself to this with passion, like I do, no. My husband, whom I met when I was 13, rarely sees me at home due to the dedication that my job requires and until now I have not had the opportunity to be a mother. I don’t see it in the short term either because we are, as it were, taking off with our research group. I am very focused at this moment on my professional career but the support of my husband and my entire family is very important for this. My partner has always shared my successes and he declares himself very proud of me, he has helped me with everything.

-I suppose that for someone who is involved in clinical research, finding a drug that saves a life must be the ultimate goal…

-For me, saving a life is a dream come true. For me, the greatest achievement of a scientist is being able to cure someone. Starting in the laboratory and ending up in the clinic.

-How would it be defined?

-As a very hard-working and very responsible person.

-And when did you start being so responsible?

-I had to be responsible from a very young age. I am eleven years older than my brother, my parents were (and are) waiters and have had to work all their lives 12 to 16 hours a day, so I had to take care of my little brother, to the point that I I had to take it to doctor’s appointments or parent meetings at school. I gave him his homework and I had to punish him.

-What did your mother say to you when she saw that you were such a good student?

-She always told me that she would like me to achieve the things that she couldn’t. I even remember that when they gave me the Seville Medal I said how could someone like me have come out of it, since she didn’t study. I don’t like her saying that at all because she knows that she has been a great role model for me in work and responsibility and I always tell her that without her constant support I would not have gotten here. I remember that when I came home from university distressed, she always cheered me up.

-Would she have liked to study at the University?

-He didn’t even have the opportunity. At 13 years old she had to leave school and go to work cleaning houses because she had to earn money to survive. Since I was born, my mother wanted for me what she had not been able to have. And as I grew older, I saw my parents working all day, including weekends and holidays, in something as hard-working as a bar, and it was clear to me that I wanted a different future for myself. I believe, in any case, that all jobs are necessary for society; The important thing, in my opinion, is to improve the conditions of all of them.

-Were you able to study thanks to the support of your family and scholarships?

-Yeah. Without scholarships she would not have been able to. And when I was studying at university, I worked summers in bars or ice cream parlors to get some money and then be able to pay my expenses during the course.

-You say that your parents worked (and work) 12 to 16 hours a day. How much time do you spend in the laboratory?

– (Smiles) I love my job because being able to help patients is the best thing, and as in all vocational jobs, time flies. I work long hours a day and I don’t usually complain, but I also want to say that vocation alone doesn’t pay the bills. Therefore, I also demand better working conditions in the health system and in the research system.

-Do you not consider yourself well paid?

-I studied Biotechnology at the Pablo de Olavide University. I was in the second year of my studies. I had more than enough marks to go into Medicine, but I was worried about my excessive empathy with patients and I was afraid of crying with them; that’s why I decided to go into the laboratory. When I finished my degree, I wanted to focus on the clinical side, not the food side, and I did a Master’s in Biomedical Research at the Institute of Biomedicine in Seville (IBIS). I started as an internal student with a scholarship and thanks to that I was able to go to Germany to do my doctoral thesis with a very cutting-edge research group. There I realised the opportunities that there were in that country for scientists and the good working conditions they enjoy there. There were also no problems with money to buy research material such as reagents, etc.

-So, we are much worse off here than in Germany.

– Worse in terms of material resources and working conditions, although we are more creative here than there. In Spain there is no such thing as a clinical researcher as in the United States or many European countries. In Germany I was paid for by the hospital, but not here. The problem for Spanish researchers who go abroad to train is returning. The chances of returning are very slim because few contracts are made and there are many people applying for them.

-But you did it.

-It was hard, but yes. Right now I have a contract with the Carlos III Health Institute in Madrid that is not linked to the Andalusian Health Service or any hospital. It is a national contract that you earn based on your CV and for which researchers from all over Spain compete. But I still don’t have job stability. I have a Miguel Servet (one of the types of contracts for researchers in Spain), which is for five years. And then I could opt for a Nicolás Monarde, but they are not permanent and we are evaluated annually. I have assumed that this is what there is in Spain and I like research too much to leave it and dedicate myself to teaching, which is the way to obtain job stability in my country. It is not that it is easy this way, but it is the way.

-In one of the last SAS examinations, the researchers were not recognized for their merits.

-We need to recognize the importance of research and I trust that this figure of the clinical researcher will be created. I achieved my research contract in 2017 and with my team we started a CAR therapy at IBIS in which we have made great progress with new designs since then (CARTemis-1). That we are already treating oncology patients with it is a dream for me. In Germany I realized how much Spanish researchers are valued and the reason is because we are very well trained. And it is a shame that you go abroad to improve your training, learn this therapy against lymphomas and other cancers, and cannot return to your country to apply it.

-What is the key for a researcher to be successful?

-Tenacity, a little luck and above all believing in what you do. And it’s crucial to surround yourself with a good team, which is what I have. There are now 9 people involved in the CAR group, apart from the hematologists. The support of IBIS and the Virgen del Rocío Hospital has been constant and fundamental for all of us.