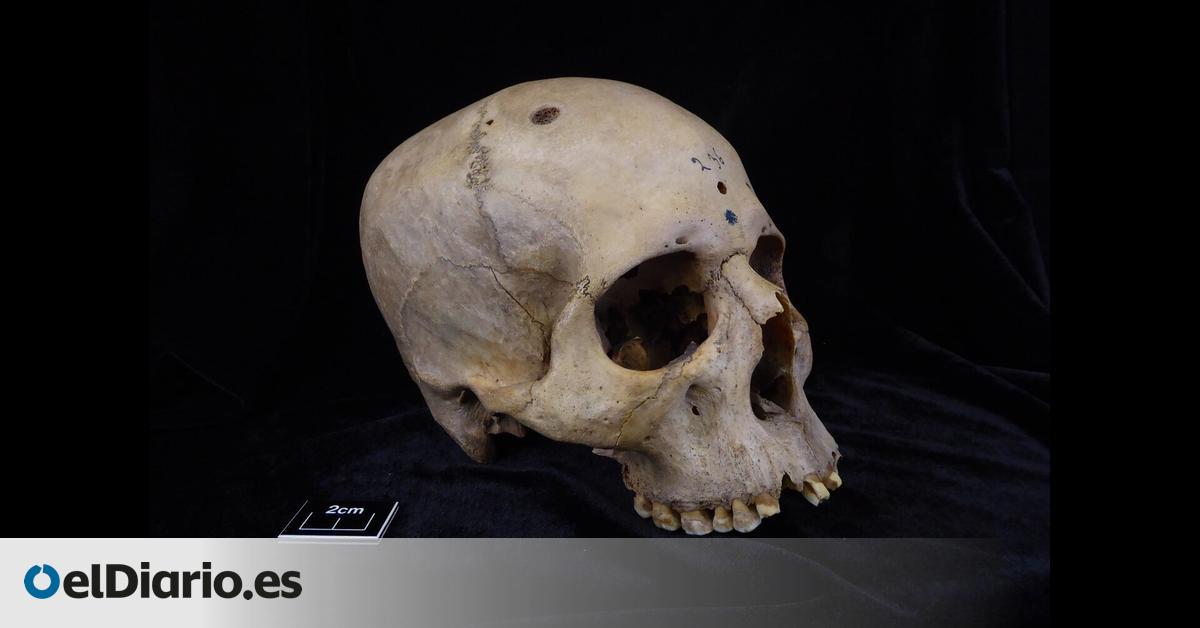

Around 4,500 years ago, the owner of skull 236, which is preserved in the collection of the Duckworth laboratory at the University of Cambridge, was a victim of nasopharyngeal cancer. The marks on the bone reveal that this man between 30 and 35 years old, whose remains were found at the beginning of the 20th century in the Giza necropolis, in Egypt, developed a tumor that advanced from the palate to the top of the head and In the process of metastasis it left several holes.

Microscopic observation allows us to document around thirty of these small, round metastatic lesions produced by cancer and distributed throughout the skull. And what is most striking when examined: in several of these injuries there are cut marks, probably made with a sharp object, a metallic instrument like the one used by Egyptian doctors from this period of the Old Kingdom, between 2687 and 2345. to. c.

“When we first looked at the cut marks under the microscope, we couldn’t believe what we had in front of us,” says Tatiana Tondini, a researcher at the University of Tübingen and first author of the study published this Wednesday in the journal Frontiers in Medicine in which the discovery is described.

The work documents the first case of medical intervention of a tumor known to date, “unique evidence of how ancient Egyptian medicine would have attempted to address or explore cancer more than 4,000 years ago,” according to Edgard Camarós, a paleopathologist at the University of Santiago de Compostela and co-author of the work. “And, although we cannot be sure whether the marks on the tumor lesions were made while the individual was alive or after the death of the individual,” warns the scientist, “in any case it is the oldest oncological intervention identified so far.”

From class to laboratory

The study also describes a second skull, less ancient than the previous one, but which inspired the beginning of the research, when Camarós worked at the University of Cambridge and used it for his classes. “Skull 270 has a huge hole, attributed to a tumor, but which had not been characterized or published,” he explains. “I used it as teaching material, as an example of a very aggressive cancer, until one day I realized and told myself: we have not studied this well. And I started reviewing the collections.”

This bone is dated between 663 and 343 BC. C. and belonged to a woman over 50 years old. The gaping hole on top is consistent with a cancerous tumor that caused bone destruction, but also traumatic injuries showing that she received some type of treatment and survived as a result.

“This case is very interesting because it shows us the limits of medical knowledge,” Camarós explains to elDiario.es. “On the left side he has a trauma that he has survived, a skull fracture that if it had not been treated would have cost him his life, but years later he developed that tumor, from which he died.” Neither in this case nor in the previous one was there any possibility of saving the patient’s life, observes the researcher, who believes that it serves as an example that we are talking about very sophisticated medicine but that it lacked the tools to confront this terrible disease.

A cancer that eats bone

“This woman survived an injury that would have killed most, but after this she had extraordinary bad luck and suffered a cranial cancer that was surely fatal, a meningosarcoma, which eats away at the bone and left the spectacular lesion in shape. of crater that it presents, of which there are only a few cases in the literature,” explains Albert Isidro, surgical oncologist at the Sagrat Cor University Hospital, specialized in Egyptology, and co-author of the study.

For Dr. Isidro, the result of this study is proof that the ancient Egyptians performed some type of surgical intervention related to the presence of cancer cells, the oldest evidence of a medical examination in relation to cancer. “There are many trepanations in the registry, some older and many of them healed, but we cannot relate them to cancer, and this one can,” says the doctor, referring to skull 236. The most relevant, in his opinion, are the striking cuts of this case – the oldest of the two -, a skull that is almost 5,000 years old.

It is impossible for these cuts to have been made by a rodent or a burrowing animal; these cuts can only and exclusively be due to an attempt to treat these injuries.

“These cuts cannot possibly have been made by a rodent or a burrowing animal; these cuts can only and exclusively be due to an attempt to treat these injuries,” asserts Albert Isidro. On the other hand, he believes that the analysis of the brands makes us think that they were perimortem, around the period of death. “The marks are not from a dry skull, they were made when the bone still had a response,” she insists. “It may be that the treatment that was attempted ended up causing the individual to die or it could not be ruled out that it was, in addition to a surgical process, a magical process, perhaps an attempt to remove evil spirits.”

The professor of Forensic Anthropology at the University of Granada, Miguel Botella, who has not participated in the study, believes that the most important thing is not only that the bone with the diagnosed cancer appears, but that there has been manipulation. “Of course, without any success, but there is a surgical intention and the marks it has are around death,” he says. In his opinion, it could almost be inferred that the subject died during this last intervention. “The tumors were very advanced, perhaps when they tried to operate on him he died,” he speculates.

The most interesting thing, says Botella, is that the study shows that there was a society that took care of very sick people unable to move. “The study, therefore, in addition to showing that the disease is already old, tells us about what the human environment that surrounded those patients was like, with conditions that reached these limits, with people who needed constant care.”

Complete cancer biography

“They didn’t even know what cancer was, they only talked about tumors,” says Edgard Camarós, who has been studying the evolution of cancer throughout history for years. The first written testimony of the existence of tumors, he recalls, is in what is known as the Edwin Smith Papyrus, dated around 1,500 BC. C. and in it an anonymous surgeon from ancient Egypt describes some cases related to breast tumors, talks about the enormous swelling and emphasizes that there is no treatment.

Camarós is convinced that this discovery will produce a change in perspective that will allow interventions to be documented even before this one. “I normally work in Africa, South America or Asia, and the irony is that one of the most interesting cases was right below the office where I worked,” he confesses. In his opinion, knowing what cancer was like in the past can be very useful to understand cancer in the present. “If we complete the biography of cancer, we will understand much better how it has evolved and, within the framework of what we call evolutionary medicine, it can help us design much better treatments,” he maintains.

The study tells us about the human environment that surrounded the sick, with patients that reached these limits, with people who needed constant care.

Thus, for example, it would be possible to understand what types of tumors were more prevalent in other times and what factors could have influenced their appearance. “There is an idea that cancer is a modern disease, but in the past it was also present, although associated with other ways of life,” says the researcher. “In desert-type environments like Egypt, for example, surrounded by sand that would cause the nasal passages to swell, nasopharyngeal cancer was very common.”

The next objective, the researchers report, is to analyze the genes of the tumors and understand what has changed in this time. “We are trying to understand and make a regressive diagnosis to see how this cancer has been changing,” highlights Camarós. “We want to know the genetic past of cancer and see which ones have survived to this day and which ones have not, to see how they have interacted with our immune system,” he summarizes. “This is what oncologists, biologists, geneticists, archaeologists and paleopathologists are working on in an interdisciplinary way, to understand cancer from the past forward and from the present backward,” he concludes.