by Carmen Phillips

The immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab (Keytruda) has quickly become one of the most widely used cancer treatments. According to the latest results from a large clinical trial, the drug is now part of a major milestone in the treatment of kidney cancer — particularly clear cell renal cell carcinoma, the most common form of the disease.

All study participants had early-stage kidney cancer with resectable tumors, but they were also at increased risk of the cancer coming back or recurring. So after surgery they were randomly assigned to receive either pembrolizumab for up to 1 year or a placebo with regular check-ups.

Four years after starting treatment after surgery, about 91% of people who received pembrolizumab were still alive, compared with 86% of those who received a placebo, according to results published April 17 in the New England Journal of MedicineOverall, people who received pembrolizumab had a nearly 40% reduced risk of death during that period.

The findings mark the first time that a post-surgery or adjuvant treatment for kidney cancer has been shown to help people live longer.

Based on the earlier results of this study, called KEYNOTE-564, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved pembrolizumab as an adjuvant treatment for kidney cancer in 2021. At the time of approval, the study had lasted long enough to show an improvement in how long people lived without their cancer coming back.

But even with the approval, many oncologists were not using pembrolizumab as a routine adjuvant treatment for their highest-risk patients, Drs. Martin Voss and Robert Motzer of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center explained in an editorial accompanying the updated findings.

Instead, they were hoping to find out whether the treatment improved people’s life expectancy overall, Drs. Voss and Motzer said. Now that we’ve answered that question, they continued, “the effect we anticipated” on patients’ daily care “has been far exceeded.”

Some experts, however, anticipate a more moderate shift in treatment. “It won’t be a complete paradigm shift,” said Dr. Mark Ball of the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Research Center, which specializes in kidney cancer treatment.

In part, that’s because the updated data also show that many patients seem to do very well with surgery alone, Dr. Ball said. He added that it’s clear that giving all patients who meet the eligibility criteria an expensive drug that could cause serious side effects would be “overtreatment.”

From a research perspective, he said, in the next steps, “We need to be smarter about identifying who is at higher risk for relapse.”

Answering the question of overall survival

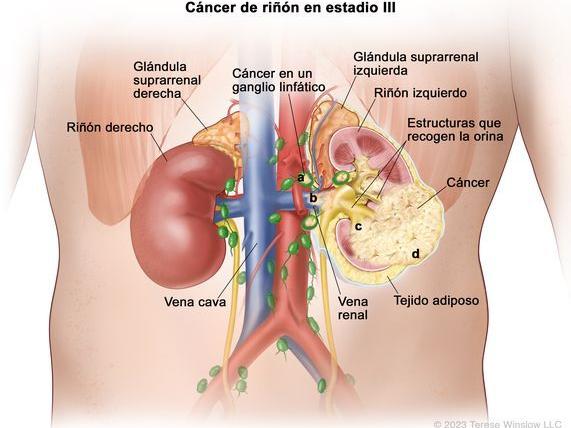

Many people with early-stage kidney cancer are cured with surgery. However, the cancer will come back in up to 50% of people, and most often in those whose cancer has certain high-risk features. These features include the presence of cancer in the lymph nodes closest to the tumor or tumor cells that look like a sarcoma.

Adjuvant therapy is used for many early-stage cancers that can be removed. It is a kind of insurance to decrease the chance that the cancer will come back by destroying cancer cells that were not removed or that leak from the tumor before surgery.

Until now, there has been only one adjuvant therapy for kidney cancer, the targeted therapy sunitinib (Sutent), which the FDA approved for this use in 2017.

That approval was based on a clinical study in which adjuvant sunitinib improved disease-free survival. But the improvement came with serious side effects, and there is no evidence that the treatment helps people live longer, Dr. Ball said.

For this reason, Dr. Ball explained, “sunitinib is never actually prescribed” for this purpose.

In the absence of proven adjuvant therapy to prolong survival in people with early-stage kidney cancer, many patients receive only periodic follow-up or monitoring.

Oncologists were therefore keen to find out whether the promise of recurrence-free survival with pembrolizumab in the KEYNOTE-564 trial would translate into improved overall survival over a longer period of time.

Improved survival at 2, 3 and 4 years

Nearly 1,000 people took part in the KEYNOTE-564 study, which was funded by Merck, the maker of pembrolizumab. All had an increased risk of their cancer coming back after surgery. Participants assigned to receive pembrolizumab took the drug every 3 weeks for up to 1 year.

At every time point during the study, other than just at 4 years, more people in the pembrolizumab group were alive.

In addition, people in the pembrolizumab group continued to live longer without their cancer coming back. At 4 years, 65% of people in the pembrolizumab group had not had a recurrence, compared with 57% in the placebo group.

| Time since start of adjuvant treatment | People in the pembrolizumab group who are still alive | People in the placebo group who are still alive |

|---|---|---|

| 2 years | 96 % | 94 % |

| 3 years | 94 % | 89.5 % |

| 4 years | 91 % | 86 % |

The findings represent “a clinically significant improvement in survival,” said the study’s lead investigator, Dr. Toni Choueiri, of the Dana-Faber Cancer Institute in Boston, when presenting the results at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Genitourinary Cancers Symposium in January 2024.

As expected, Dr. Choueiri noted, more people in the pembrolizumab group had treatment-related side effects, such as fatigue and rash, which are typically seen in people treated with the drug.

Overall, about 20% of people in the pembrolizumab group had serious side effects, and 21% stopped treatment early because of side effects (as did 2% of people in the placebo group).

A major change in the treatment of early-stage kidney cancer?

More people with early-stage renal cell cancer should now receive pembrolizumab after surgery, Dr. Pedro Barata of the Seidman Cancer Center in Cleveland, a kidney cancer specialist, said at the ASCO Genitourinary Cancers Symposium.

Dr. Barata said he typically recommends adjuvant pembrolizumab therapy for patients who are at very high risk of their cancer coming back, which he assesses using a kidney cancer recurrence risk model.

Most patients will have only mild side effects from the treatment, he continued. But “other patients will have serious side effects,” and the treatments to manage those side effects produce their own side effects.

Oncologists therefore need to discuss potential improvements in survival versus potential side effects, Dr. Barata noted.

“We have to take into account quality of life, patient preferences and even drug availability in some cases,” he explained. “However, I would say that [ahora] The results favor the use of adjuvant pembrolizumab.”

Dr. Ball agreed. Moreover, unlike other cancers for which pembrolizumab is a standard treatment, there are no tumor or blood markers (biomarkers) that identify patients whose cancer would respond best to the drug.

So for now, oncologists must rely on proven risk factors when guiding treatment decisions and recommendations for their patients, he added.